Why President Coolidge Never Ate His Thanksgiving Raccoon by Luke Fater

Nov 23, 2023 13:53:20 #

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/did-president-always-pardon-turkey?

A tradition as American as apple pie, and older than the Constitution.

In November of 1926, a woman from Mississippi sent President Calvin Coolidge a raccoon for Thanksgiving. An accompanying note promised that it had, in her words, a “toothsome flavor.” The story of the day, however, was not that Coolidge received a raccoon for dinner, but rather that he declined to eat it. “Coolidge Has Raccoon; Probably Won’t Eat It,” read The Boston Herald.

Indeed, countless other raccoons throughout American history did not share such a lucky fate as Coolidge’s pardoned critter. Raccoon meat is a longstanding American culinary staple that went from “slave food” to New York City markets to cookbooks across the country. The critters that once sustained entire regions have disappeared from most modern dinner tables, but not all of them.

Written documents outlining Native American diets are scant, but it’s more than apparent that the practice of eating raccoon originated with them and was later handed down to enslaved African people across the American South. Michael Twitty, James Beard Award-winning author of The Cooking Gene, points out that the word itself comes from the term aroughcun, Powhatan for “hand-scratcher,” which in the mouths of many West Africans, who have no “r” sound in their language, became the antiquated but colloquially known “coon.”

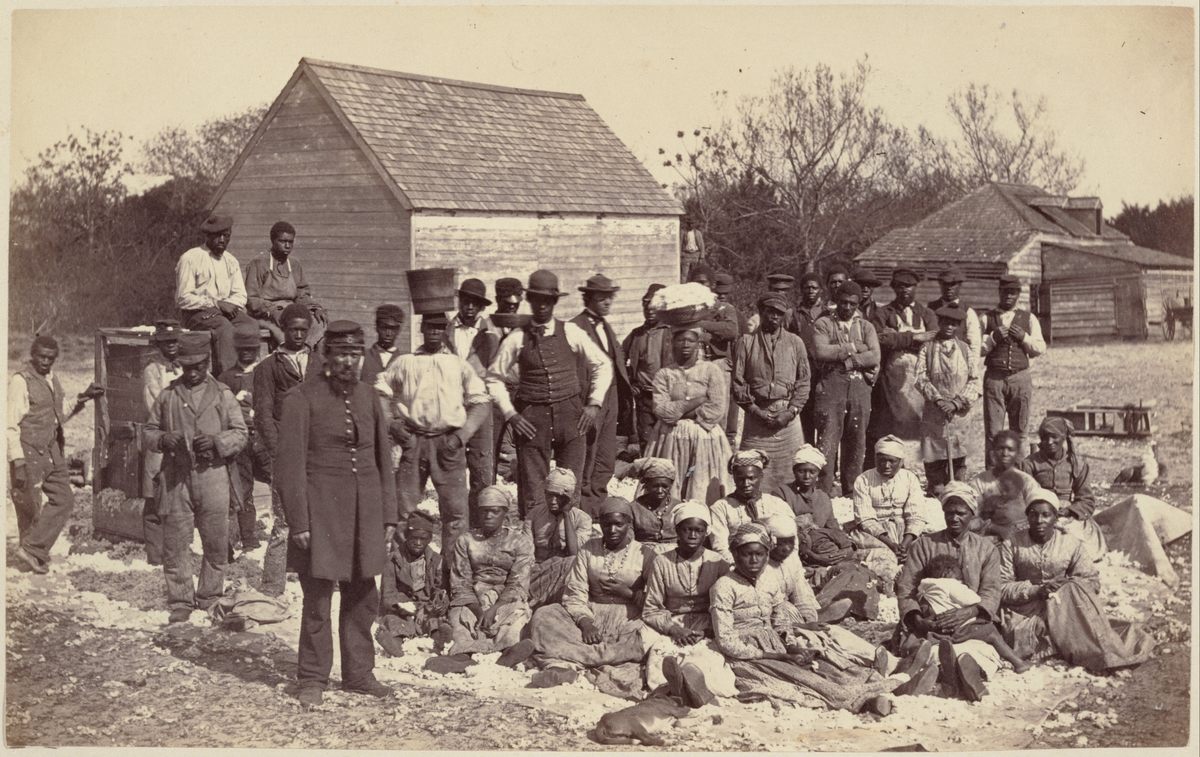

Enslaved African people throughout the American South incorporated raccoon into their daily diets to supplement the meager provisions offered on plantations. They were no strangers to small-game hunting: The raccoons of North America behave much like the grasscutters of West Africa, a similarly nocturnal bush rodent that Africans had trapped and eaten for centuries. “They were master trappers,” says Twitty. “In fact, some of the traps enslaved people used are mirror images of traps from West Africa, if not similar to traps that Native Americans used.”

Enslavers approved of the practice. “The slaves weren’t allowed to hunt during the daytime,” says Hank Shaw, author of Hunt, Gather, Cook. “So after they’d finish their workday, they were permitted to hunt in the middle of the night to get some extra protein in their diet.” By granting enslaved African people raccoon meat trapped with techniques that fused African and Native American methods, slave owners could keep their slaves well-fed without the risk of arming them. Archaeological evidence pulled from plantations between Florida and Virginia indicates that whole raccoons were often cooked in stews—an echo of West African culinary memory reverberating across the Eastern seaboard.

“It’s not a big leap to think about my ancestors—coming from a place of utilizing everything that’s edible—making contact with another group of people with a similar way of life,” says Twitty of the Native to African raccoon transmission, “and then transferring these traditions onto white Americans.”

Throughout the late 1800s, the tradition of eating raccoon saturated the national food-scape, as westward settlement across the Appalachians met the northward march of newly free Black Americans. “If you were a poor white person, you were cohabitating with an African or a native person,” says Twitty. “And if they were making raccoon for dinner, that’s what everybody was eating.”

Dr. Megan Elias, a historian and gastronomist from Boston University, writes that small game such as raccoons and squirrels simultaneously fed frontier families and supplied added income in the burgeoning fur trade. Culinary historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson writes that eating raccoons—nuisance animals apt to ravage vegetable fields—also kept crop yields robust. “With every bit of food raised needed to get through the winter, pest animals became not only fair game, but good eating, too.”

After emerging as a food of necessity, raccoon enjoyed its day in the middle-class American sun. It was sold in game markets all the way up to New York City, both alive and dead. It made its way onto restaurant menus from Maine to Louisville and into cookbooks from Colorado to Vermont. Johnson writes that hunting even became a popular nighttime social event among men who bred “coonhounds” that chased the animals into treetops to be easily shot. And by 1926, of course, raccoon was food fit for a president.

With the proliferation of factory farming through the 1900s, however, Americans reconsidered their meat preferences. Urbanites abandoned small game like raccoon, which was laced with unfavorable racial and class stigmas, in favor of cheap pork, chicken, and beef. “It belies the fact that without those measures, a lot of poor whites wouldn’t have survived,” says Twitty of the raccoon stigma. Black Americans largely deserted the critters as well. “When black folks in America moved from the country to the city, the raccoon went the way of the banjo,” says Twitty. “It’s a relic of a time we didn’t really want to associate ourselves with.”

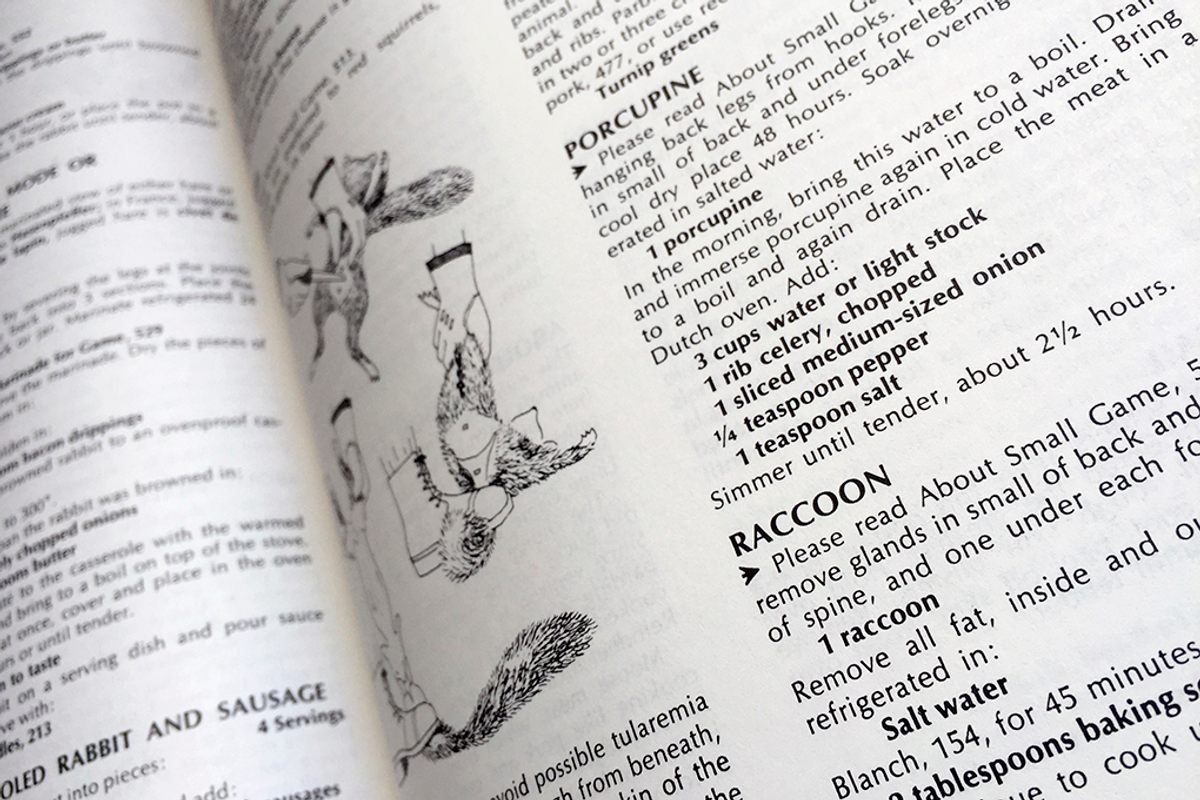

Nonetheless, having supported entire regions of underprivileged Americans for centuries, raccoon indelibly worked its way into the American culinary psyche. Preparation instructions for raccoon carcasses appeared in multiple editions of The Joy of Cooking throughout the 1900s. Raccoon hunting itself became an icon of rural American life, if Dolly Parton lyrics mean nothing else. Shaw says the propagation of coonhounds kept the tradition of nighttime raccoon hunts alive in the Appalachian South. He adds that word-of-mouth raccoon meat markets stretched throughout the Midwest as a byproduct of trapping, where colder weather meant lusher fur. “Best kept secret around,” an 86-year-old Missourian told the Kansas City Star in 2009 over a trunk full of frozen raccoon carcasses in a thrift store parking lot.

The tradition today survives in rural, economically distressed communities, often as fund-raising events. The 93rd annual “Coon Feed” in Delafield, Wisconsin, last year served more than 300 plates of raccoon to raise money for area veterans. The 76th annual “Coon Supper” in Gillett, Arkansas this past January raised money to send a small-town student to college; the event has also become something of a bureaucratic initiation where aspiring local politicians ingratiate themselves to rural voters by eating varmint on camera. “They literally serve raccoon. And you’re supposed to eat some,” GOP Rep. Rick Crawford told Roll Call in 2014. “That’s the tradition.”

As for Coolidge, his refusal to eat raccoon earned him a family pet. For Christmas of 1926, he gave the “toothsome,” hand-scratching, would-be entree a steel-plated collar with her name engraved: Rebecca. She lived with the Coolidges for the remainder of Silent Cal’s term, taking a liking to corn muffins and, as First Lady Grace Coolidge wrote, “playing in a partly filled bathtub with a cake of soap.”

Rebecca was donated to the Rock Creek Park Zoo in 1928 to live out her days among other raccoons, though her days of presidential extravagance cursed her with a refined palette and an intolerance to wild animals. She quickly grew ill and died, though, of course, it could have been worse. She could have been a turkey.

A tradition as American as apple pie, and older than the Constitution.

In November of 1926, a woman from Mississippi sent President Calvin Coolidge a raccoon for Thanksgiving. An accompanying note promised that it had, in her words, a “toothsome flavor.” The story of the day, however, was not that Coolidge received a raccoon for dinner, but rather that he declined to eat it. “Coolidge Has Raccoon; Probably Won’t Eat It,” read The Boston Herald.

Indeed, countless other raccoons throughout American history did not share such a lucky fate as Coolidge’s pardoned critter. Raccoon meat is a longstanding American culinary staple that went from “slave food” to New York City markets to cookbooks across the country. The critters that once sustained entire regions have disappeared from most modern dinner tables, but not all of them.

Written documents outlining Native American diets are scant, but it’s more than apparent that the practice of eating raccoon originated with them and was later handed down to enslaved African people across the American South. Michael Twitty, James Beard Award-winning author of The Cooking Gene, points out that the word itself comes from the term aroughcun, Powhatan for “hand-scratcher,” which in the mouths of many West Africans, who have no “r” sound in their language, became the antiquated but colloquially known “coon.”

Enslaved African people throughout the American South incorporated raccoon into their daily diets to supplement the meager provisions offered on plantations. They were no strangers to small-game hunting: The raccoons of North America behave much like the grasscutters of West Africa, a similarly nocturnal bush rodent that Africans had trapped and eaten for centuries. “They were master trappers,” says Twitty. “In fact, some of the traps enslaved people used are mirror images of traps from West Africa, if not similar to traps that Native Americans used.”

Enslavers approved of the practice. “The slaves weren’t allowed to hunt during the daytime,” says Hank Shaw, author of Hunt, Gather, Cook. “So after they’d finish their workday, they were permitted to hunt in the middle of the night to get some extra protein in their diet.” By granting enslaved African people raccoon meat trapped with techniques that fused African and Native American methods, slave owners could keep their slaves well-fed without the risk of arming them. Archaeological evidence pulled from plantations between Florida and Virginia indicates that whole raccoons were often cooked in stews—an echo of West African culinary memory reverberating across the Eastern seaboard.

“It’s not a big leap to think about my ancestors—coming from a place of utilizing everything that’s edible—making contact with another group of people with a similar way of life,” says Twitty of the Native to African raccoon transmission, “and then transferring these traditions onto white Americans.”

Throughout the late 1800s, the tradition of eating raccoon saturated the national food-scape, as westward settlement across the Appalachians met the northward march of newly free Black Americans. “If you were a poor white person, you were cohabitating with an African or a native person,” says Twitty. “And if they were making raccoon for dinner, that’s what everybody was eating.”

Dr. Megan Elias, a historian and gastronomist from Boston University, writes that small game such as raccoons and squirrels simultaneously fed frontier families and supplied added income in the burgeoning fur trade. Culinary historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson writes that eating raccoons—nuisance animals apt to ravage vegetable fields—also kept crop yields robust. “With every bit of food raised needed to get through the winter, pest animals became not only fair game, but good eating, too.”

After emerging as a food of necessity, raccoon enjoyed its day in the middle-class American sun. It was sold in game markets all the way up to New York City, both alive and dead. It made its way onto restaurant menus from Maine to Louisville and into cookbooks from Colorado to Vermont. Johnson writes that hunting even became a popular nighttime social event among men who bred “coonhounds” that chased the animals into treetops to be easily shot. And by 1926, of course, raccoon was food fit for a president.

With the proliferation of factory farming through the 1900s, however, Americans reconsidered their meat preferences. Urbanites abandoned small game like raccoon, which was laced with unfavorable racial and class stigmas, in favor of cheap pork, chicken, and beef. “It belies the fact that without those measures, a lot of poor whites wouldn’t have survived,” says Twitty of the raccoon stigma. Black Americans largely deserted the critters as well. “When black folks in America moved from the country to the city, the raccoon went the way of the banjo,” says Twitty. “It’s a relic of a time we didn’t really want to associate ourselves with.”

Nonetheless, having supported entire regions of underprivileged Americans for centuries, raccoon indelibly worked its way into the American culinary psyche. Preparation instructions for raccoon carcasses appeared in multiple editions of The Joy of Cooking throughout the 1900s. Raccoon hunting itself became an icon of rural American life, if Dolly Parton lyrics mean nothing else. Shaw says the propagation of coonhounds kept the tradition of nighttime raccoon hunts alive in the Appalachian South. He adds that word-of-mouth raccoon meat markets stretched throughout the Midwest as a byproduct of trapping, where colder weather meant lusher fur. “Best kept secret around,” an 86-year-old Missourian told the Kansas City Star in 2009 over a trunk full of frozen raccoon carcasses in a thrift store parking lot.

The tradition today survives in rural, economically distressed communities, often as fund-raising events. The 93rd annual “Coon Feed” in Delafield, Wisconsin, last year served more than 300 plates of raccoon to raise money for area veterans. The 76th annual “Coon Supper” in Gillett, Arkansas this past January raised money to send a small-town student to college; the event has also become something of a bureaucratic initiation where aspiring local politicians ingratiate themselves to rural voters by eating varmint on camera. “They literally serve raccoon. And you’re supposed to eat some,” GOP Rep. Rick Crawford told Roll Call in 2014. “That’s the tradition.”

As for Coolidge, his refusal to eat raccoon earned him a family pet. For Christmas of 1926, he gave the “toothsome,” hand-scratching, would-be entree a steel-plated collar with her name engraved: Rebecca. She lived with the Coolidges for the remainder of Silent Cal’s term, taking a liking to corn muffins and, as First Lady Grace Coolidge wrote, “playing in a partly filled bathtub with a cake of soap.”

Rebecca was donated to the Rock Creek Park Zoo in 1928 to live out her days among other raccoons, though her days of presidential extravagance cursed her with a refined palette and an intolerance to wild animals. She quickly grew ill and died, though, of course, it could have been worse. She could have been a turkey.

First Lady Grace Coolidge in 1926 with what was meant to be dinner. Library of Congress/LC-DIG-npcc-16730

Hunter John Wilson, who sells thousands of raccoon carcasses each year to people who continue to eat the animal, prepares raccoon pelts in Freeport, Illinois. Alex Garcia/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Enslaved African people employed ancestral trapping techniques to fend off starvation under grueling conditions on slave plantations throughout the American South. Henry P. Moore/Public Domain

Before rabies and suburbanization, raccoons held fewer negative associations, finding themselves at home on America’s dinner tables, in one way or another. age fotostock / Alamy

Instructions for preparing raccoon stew made it into multiple publications of Irma S. Rombauer’s The Joy of Cooking, pictured here in the 1975 edition. Krissie Mason/used with permission

Fur trappers throughout the bitter Midwest—where raccoon pelts are lush—often sell the meat as a byproduct, leaving one paw attached by law to distinguish the carcasses from those of cats. age fotostock / Alamy

Rebecca the Raccoon often escaped her cage and led White House aides on hours-long pursuits around the property. Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-100816

Nov 23, 2023 14:18:21 #

bikinkawboy

Loc: north central Missouri

Don’t worry about running out of raccoons. My young coworker traps and captured 230 of them last winter. He started trapping this earlier this week and hopes to have 50 by Monday. Ends up the more individuals you remove from an area, the larger the litters are, meaning you never run out of them. Plus others move in.

Nov 23, 2023 14:21:14 #

Nov 23, 2023 14:23:12 #

Nov 23, 2023 18:00:21 #

bikinkawboy wrote:

Don’t worry about running out of raccoons. My young coworker traps and captured 230 of them last winter. He started trapping this earlier this week and hopes to have 50 by Monday. Ends up the more individuals you remove from an area, the larger the litters are, meaning you never run out of them. Plus others move in.

What does he do with them?

What does he do with them?Nov 23, 2023 18:00:57 #

MosheR wrote:

Thanks, Brian. I'll stick with turkey.

You and me both Mel although I prefer ham to turkey.

Nov 23, 2023 18:01:14 #

Nov 23, 2023 18:41:24 #

jimkolt

Loc: Sun City, AZ

Interesting. Growing up in Illinois, we had neighbors who would occasionally hunt raccoons, but I thought they only wanted the pelts. Not sure if they ate them or not.

Nov 23, 2023 19:11:12 #

bikinkawboy

Loc: north central Missouri

bcheary wrote:

What does he do with them?

What does he do with them?

What does he do with them?

What does he do with them?He’s only interested in the pelts. He does sometimes grind up some to feed his bird dogs but most he leaves for eagles and other scavengers.

Nov 23, 2023 19:15:51 #

bikinkawboy wrote:

He’s only interested in the pelts. He does sometimes grind up some to feed his bird dogs but most he leaves for eagles and other scavengers.

Nov 23, 2023 21:08:55 #

rwww80a

Loc: Hampton, NH

Up here in New England they are usually infested with ticks and rabies. Not sure if I would gobble one down.

Nov 24, 2023 04:56:40 #

Fortunately, rabies is not a prion driven disease, which is in protein, so eating a rabid raccoon will not kill you. This is significant since there is a high incidence of rabies among raccoons.

Nov 24, 2023 07:50:10 #

Nov 24, 2023 08:06:27 #

rwww80a

Loc: Hampton, NH

SteveR wrote:

Fortunately, rabies is not a prion driven disease, which is in protein, so eating a rabid raccoon will not kill you. This is significant since there is a high incidence of rabies among raccoons.

BUT

did the ethnic, poor and native American's know this in the 17th and 18th centauries.

Nov 24, 2023 09:06:53 #

Eyes

Loc: Buffalo, NY

MosheR wrote:

Thanks, Brian. I'll stick with turkey.

I Completely Agree!

Can say that I DID have 'coon many yrs ago. Everybody thought it was quite greasy (fatty anyway....). Too bad actually, cuz the critters yrs ago made a Hotel out of my barn. Get them on-camera abt every night!

Carl

If you want to reply, then register here. Registration is free and your account is created instantly, so you can post right away.