I spy with my Cold War satellite eye… nearly 400 Roman forts in the Middle East by Jennifer Ouellette -

Oct 31, 2023 16:41:25 #

https://arstechnica.com/science/2023/10/i-spy-with-my-cold-war-satellite-eye-nearly-400-roman-forts-in-the-middle-east/?

Anthropologists suggest forts were built to secure key trade routes through the region.

Back in the early days of aerial archaeology, a French Jesuit priest named Antoine Poidebard flew a biplane over the northern Fertile Crescent to conduct one of the first aerial surveys. He documented 116 ancient Roman forts spanning what is now western Syria to northwestern Iraq and concluded that they were constructed to secure the borders of the Roman Empire in that region.

Now, anthropologists from Dartmouth have analyzed declassified spy satellite imagery dating from the Cold War, identifying 396 Roman forts, according to a recent paper published in the journal Antiquity. And they have come to a different conclusion about the site distribution: the forts were constructed along trade routes to ensure the safe passage of people and goods.

Poidebard is a fascinating historical figure. A former World War I pilot, he later became a priest and joined the French Levant forces, helping pioneer the use of aerial photography as an archaeological surveying tool to discover and record sites of interest. (Previously, hot air balloons, scaffolds, or attaching cameras to kites were the primary means of gaining aerial context.) For his mapping missions, Poidebard clocked thousands of hours flying over Syria, as well as Algeria and Tunisia along the Mediterranean coast. He published his catalog of ancient Roman forts in his 1934 book, The Trace of Rome in the Syrian Desert, including some of the largest and best-known sites, including Sura, Resafa, and Ain Sinu.

Poidebard's map showed the fort sites roughly running in a north-south line along the eastern boundary of the Roman Empire. This corresponded with a road built under the emperor Diocletian (284–305 CE) known as the strata Diocletiana. Poidebard believed the forts were mostly constructed during the second and third centuries CE as a border wall to defend the eastern Roman provinces from invasions by Arab nomads or Persian armies. But later scholars argued that the forts were too far apart to function efficiently as a border wall, suggesting instead that they had been used to protect military and commercial caravans in the region—or possibly to defend local populations from nomadic raids.

This latest study bolsters the latter hypothesis, with the authors attributing Poidebard's original conclusions to discovery bias. "He flew his biplane over areas where he believed forts would most likely be located and found many of them, seemingly confirming his theory of their function in fortifying the Roman limes [border]," they wrote.

It's difficult to perform ground-based archaeological exploration of these sites, given the region's long history of war and conflict. That's where the spy satellite imagery has proven to be a crucial tool. The authors used declassified imagery from the CORONA and HEXAGON programs to monitor the Soviet Union, China, and other strategic areas from 1959 through 1972—part of the US response to the USSR's successful launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957. The imagery was declassified in the 1990s and early 2000s and is maintained by the US Geological Survey.

Archaeologists have embraced this new resource. For instance, Harvard University researchers have analyzed the imagery to identify prehistoric traveling routes through Mesopotamia. And in 2006, a team from the Australian National University found evidence of early Islamic pottery factories, along with a hilltop complex of megalithic tombs and the identification of Middle Paleolithic remains at the ancient fortress site of Jebel Khalid in the Euphrates River Valley.

The Dartmouth team analyzed CORONA and HEXAGON images covering some 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 square miles) in the northern Fertile Crescent, mapping 4,500 known archaeological sites and other features that seemed to be sites of interest. Some 10,000 previously undiscovered sites were added to their database. Poidebard's forts have their own category in that database, based on their distinctive square shape and size, and the Dartmouth researchers found many more likely forts lurking in the spy satellite imagery.

The results confirmed Poidebard's 1934 finding of a line of forts running along the strata Dioceltiana and also revealed several new forts along that route. But the survey also showed many new, previously undetected Roman forts running west-southwest between the Euphrates Valley and western Syria, as well as connecting the Tigris and Khabur rivers. That seems more suggestive of the forts supporting the movement of troops, supplies, or trade goods across the Fertile Crescent—cultural exchange sites rather than barriers. The authors date most of the forts to between the second and sixth centuries CE, after which there was widespread abandonment of the sites, although a few remained occupied into the medieval period.

"I was surprised to find that there were so many forts and that they were distributed in this way because the conventional wisdom was that these forts formed the border between Rome and its enemies in the east, Persia or Arab armies," said co-author Jesse Casana, an anthropologist and director of the Spatial Archaeometry Lab at Dartmouth. "While there's been a lot of historical debate about this, it had been mostly assumed that this distribution was real, that Poidebard's map showed that the forts were demarcating the border and served to prevent movement across it in some way."

Anthropologists suggest forts were built to secure key trade routes through the region.

Back in the early days of aerial archaeology, a French Jesuit priest named Antoine Poidebard flew a biplane over the northern Fertile Crescent to conduct one of the first aerial surveys. He documented 116 ancient Roman forts spanning what is now western Syria to northwestern Iraq and concluded that they were constructed to secure the borders of the Roman Empire in that region.

Now, anthropologists from Dartmouth have analyzed declassified spy satellite imagery dating from the Cold War, identifying 396 Roman forts, according to a recent paper published in the journal Antiquity. And they have come to a different conclusion about the site distribution: the forts were constructed along trade routes to ensure the safe passage of people and goods.

Poidebard is a fascinating historical figure. A former World War I pilot, he later became a priest and joined the French Levant forces, helping pioneer the use of aerial photography as an archaeological surveying tool to discover and record sites of interest. (Previously, hot air balloons, scaffolds, or attaching cameras to kites were the primary means of gaining aerial context.) For his mapping missions, Poidebard clocked thousands of hours flying over Syria, as well as Algeria and Tunisia along the Mediterranean coast. He published his catalog of ancient Roman forts in his 1934 book, The Trace of Rome in the Syrian Desert, including some of the largest and best-known sites, including Sura, Resafa, and Ain Sinu.

Poidebard's map showed the fort sites roughly running in a north-south line along the eastern boundary of the Roman Empire. This corresponded with a road built under the emperor Diocletian (284–305 CE) known as the strata Diocletiana. Poidebard believed the forts were mostly constructed during the second and third centuries CE as a border wall to defend the eastern Roman provinces from invasions by Arab nomads or Persian armies. But later scholars argued that the forts were too far apart to function efficiently as a border wall, suggesting instead that they had been used to protect military and commercial caravans in the region—or possibly to defend local populations from nomadic raids.

This latest study bolsters the latter hypothesis, with the authors attributing Poidebard's original conclusions to discovery bias. "He flew his biplane over areas where he believed forts would most likely be located and found many of them, seemingly confirming his theory of their function in fortifying the Roman limes [border]," they wrote.

It's difficult to perform ground-based archaeological exploration of these sites, given the region's long history of war and conflict. That's where the spy satellite imagery has proven to be a crucial tool. The authors used declassified imagery from the CORONA and HEXAGON programs to monitor the Soviet Union, China, and other strategic areas from 1959 through 1972—part of the US response to the USSR's successful launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957. The imagery was declassified in the 1990s and early 2000s and is maintained by the US Geological Survey.

Archaeologists have embraced this new resource. For instance, Harvard University researchers have analyzed the imagery to identify prehistoric traveling routes through Mesopotamia. And in 2006, a team from the Australian National University found evidence of early Islamic pottery factories, along with a hilltop complex of megalithic tombs and the identification of Middle Paleolithic remains at the ancient fortress site of Jebel Khalid in the Euphrates River Valley.

The Dartmouth team analyzed CORONA and HEXAGON images covering some 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 square miles) in the northern Fertile Crescent, mapping 4,500 known archaeological sites and other features that seemed to be sites of interest. Some 10,000 previously undiscovered sites were added to their database. Poidebard's forts have their own category in that database, based on their distinctive square shape and size, and the Dartmouth researchers found many more likely forts lurking in the spy satellite imagery.

The results confirmed Poidebard's 1934 finding of a line of forts running along the strata Dioceltiana and also revealed several new forts along that route. But the survey also showed many new, previously undetected Roman forts running west-southwest between the Euphrates Valley and western Syria, as well as connecting the Tigris and Khabur rivers. That seems more suggestive of the forts supporting the movement of troops, supplies, or trade goods across the Fertile Crescent—cultural exchange sites rather than barriers. The authors date most of the forts to between the second and sixth centuries CE, after which there was widespread abandonment of the sites, although a few remained occupied into the medieval period.

"I was surprised to find that there were so many forts and that they were distributed in this way because the conventional wisdom was that these forts formed the border between Rome and its enemies in the east, Persia or Arab armies," said co-author Jesse Casana, an anthropologist and director of the Spatial Archaeometry Lab at Dartmouth. "While there's been a lot of historical debate about this, it had been mostly assumed that this distribution was real, that Poidebard's map showed that the forts were demarcating the border and served to prevent movement across it in some way."

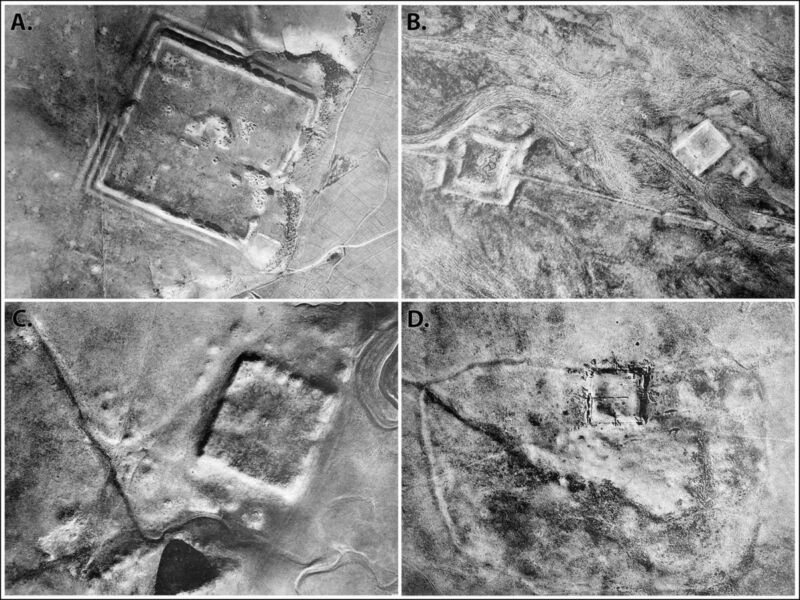

Spy satellite images taken by the CIA during the Cold War have revealed hundreds of Roman forts across the Fertile Crescent.

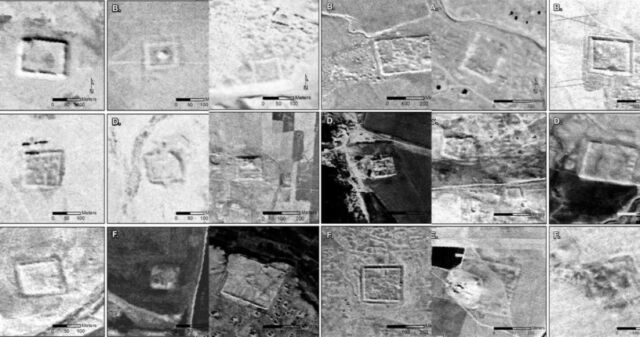

More spy satellite images showing sites of probable Roman forts.

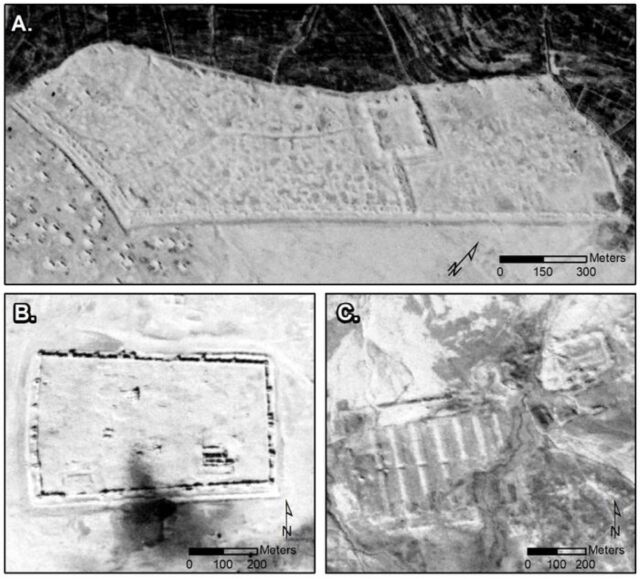

CORONA images showing major sites: A) Sura (NASA1401); B) Resafa (NASA1398); and C) Ain Sinu (CRN999).

Nov 1, 2023 06:56:28 #

Pretty interesting! The Roman Empire was pretty amazing - they built roads, aqueducts, buildings, and forts throughout their range of influence. They were fascinated by the cultures and religions in the Middle East - it is surprising for me to see in Rome 17 huge Egyptian obelisks scattered throughout Rome in various plazas, all covered with hieroglyphics. One, I was told, was so large and heavy that it was strapped sideways across three ships that were linked together side-by-side.

Nov 1, 2023 08:56:44 #

sb wrote:

Pretty interesting! The Roman Empire was pretty amazing - they built roads, aqueducts, buildings, and forts throughout their range of influence. They were fascinated by the cultures and religions in the Middle East - it is surprising for me to see in Rome 17 huge Egyptian obelisks scattered throughout Rome in various plazas, all covered with hieroglyphics. One, I was told, was so large and heavy that it was strapped sideways across three ships that were linked together side-by-side.

Interesting.

Nov 1, 2023 12:59:59 #

bcheary wrote:

When on the March the Roman's would build fortifications every night they stopped. The fortifications were oriented the same every time and each unit occupied the same position within the fortifications every time and each man was to be found in the same position. All for the ease of command and communication if the need arose. They were prolific builders and engineers. Their feats of construction make good reading and will amaze you. Read Caesars diary of the Gallic campaign.

Nov 1, 2023 16:58:52 #

Nov 2, 2023 08:53:12 #

MosheR

Loc: New York City

bcheary wrote:

That's one of the reasons the Roman Empire became so widespread and lasted as long as it did.

Nov 2, 2023 11:27:32 #

MosheR wrote:

That's one of the reasons the Roman Empire became so widespread and lasted as long as it did.

If you want to reply, then register here. Registration is free and your account is created instantly, so you can post right away.