B&W Ruminations - Why T-Max et. al.

Dec 27, 2017 11:00:10 #

Rich, I just did a guick search for the first digital camera. All of the hits were Kodak and Steve Sasson.

As for the chain of events that followed, Wikipedia has a pretty comprehensive history of the camera, which includes digital. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_camera

--Bob

As for the chain of events that followed, Wikipedia has a pretty comprehensive history of the camera, which includes digital. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_camera

--Bob

Rich1939 wrote:

I believe a "film less" camera was first patented by an engineer at Texas Instruments earlier than that (1972). However the first digital camera announced for consumer sales was from Nikon around the same time as T-Max was introduced but, when I got out of the retail end of the game in late '88 deliveries still hadn't started.

Dec 27, 2017 11:52:17 #

clint f.

Loc: Priest Lake Idaho, Spokane Wa

anotherview wrote:

For digital photographers, both Adobe Photoshop and third-party vendors resolve this matter, by way of filters and adjustments that emulate the look of film.

I’m reminded of the Harley Davidson vs Imported “cruisers” where they say “it looks like or sounds just like a Harley.” Here it’s “looks just like film.” There is always a standard to which all is compared, personal preferences aside.

Dec 27, 2017 12:04:46 #

bpulv

Loc: Buena Park, CA

Shutterbug57 wrote:

First off, this is not a film is better than digit... (show quote)

Growing up in a digital world, you got it backwards. In fact, in the pre-digital world grain was considered the enemy. We played a tradeoff game between high ISO and grain. The higher the ISO of the film, the larger and more objectionable the grain. I remember when Kodak had three main emulsions that most photographers used. Plus-X was a medium speed film (I think it was ASA 125?) with medium grain, Tri-X was the fast ISO 400 or ISO 360 film with more pronounced grain and Panatomic-X was an ISO 32 film that was used when small grain was essential. There were many other films too such as Royal-X pan that had a very high ASA; 1600 if I recall correctly. Its grain was like golf balls by comparison to Tri-X. Those were the most used films for 35mm and medium format. If you counted the sheet film types, there were more that two dozen. One of the many reasons that the 4 X 5" format was popular in those days was that less enlargement was require to make a given size print and therefore the grain was enlarged less and in most cases not noticeable.

As time went by, Kodak and others came out with developers such as Microdol and much later T-Max that produced smaller grain with existing films, but we could never completely eliminate the enemy, grain.

The fact is that the desire for a grainy look today has grown out of a nostalgia for something that was undesirable in its own time.

Dec 27, 2017 12:47:41 #

bpulv wrote:

Growing up in a digital world, you got it backward... (show quote)

Sure, there were a lot of fine grain advocates back in the day, but there are also photographers who liked the grain of Tri-X, and would shoot it even if they didn't need the speed, myself included. Robert Frank was a hero back then, and people loved the grainy look of his photos. I like the look of grainy film much better than digital noise.

Dec 27, 2017 13:07:24 #

Cletus

Loc: Mongolia

A factoid that illustrates how our view (no pun intended) of photography changes over time: When digital first began to reach the wider public consciousness, people in the industry called it by another name ... maybe to help people comprehend it better. A name you can still see if you dig into the advertising of that era. It was called "still video." And the very first consumer digital cameras produced photos with visible rows of pixels over the entire image ... resolution that wouldn't be acceptable today even on the cheapest TV screen. At the same time, film technology was at its zenith, with the arrival of amazing emulsions such as Velvia.

Dec 27, 2017 13:12:32 #

Jeffc: Tech Pan film was great but there were 2 films even finer grain. Kodak High Contrast Copy HCC was one. Using this type film for normal photography with a special developer originally started with a private individual (not Kodak) who I met. I could get 240 lines/mm on the standard resolution chart with my best lens the Leica Summicron F2 (their binoculars were always better too) but only 200 lines/mm with Tech Pan. With Pan X all the best lenses topped out at 100 lines/mm (it was not fine grain enough for lens testing). Film resolution has been the biggest detriment to resolution all these years--not the lenses. Then Kodak tried to play catch up & has to lower everything to their standards for the public with Tech Pan. I didn't have to carry a 4x5 or a 8x10 anymore to make big enlargements with HCC but Tech Pan was better than Pan X.

But the finest grain film of all was Spectrographic 649 that Kodak said would resolve 1000 (?) lines/mm & I had 50' of it 40 years ago. I got 400 lines/mm with that film. I made magnificent enlargements with it & no grain in really big ones with the original developer used on HCC. I won bets with it claiming it was shot in a 35MM camera but had to show the negs. You could barely see grain in a microscope. The ASA or ISO was about .05 to 1 & for simplicity I took a light meter reading at ISO 25 & multiplied the exposure time by 10--not exactly hand held.

Kodak had a special film in jets they claimed they could take a license plate over a car from some number of miles (?) over it. If so the plane would have to be at around 45 degrees in front 30% further (maybe a helicopter to reduce movement) or have some magic right angle prisms in the film to read the plates & a vary fast ISO when flying at jet speed over the car! I tried to get some but never could. They asked me how high I wanted to take pictures & I said 5' 3". He didn't understand me & I had to explain. He told me I was the only one who ever wanted it for normal photography.

That last smaller negative camera they came out with followed their lowering everything to their standards approach to the public. If you held the prints out at arms length they were just tolerable but you never kept them.

But the finest grain film of all was Spectrographic 649 that Kodak said would resolve 1000 (?) lines/mm & I had 50' of it 40 years ago. I got 400 lines/mm with that film. I made magnificent enlargements with it & no grain in really big ones with the original developer used on HCC. I won bets with it claiming it was shot in a 35MM camera but had to show the negs. You could barely see grain in a microscope. The ASA or ISO was about .05 to 1 & for simplicity I took a light meter reading at ISO 25 & multiplied the exposure time by 10--not exactly hand held.

Kodak had a special film in jets they claimed they could take a license plate over a car from some number of miles (?) over it. If so the plane would have to be at around 45 degrees in front 30% further (maybe a helicopter to reduce movement) or have some magic right angle prisms in the film to read the plates & a vary fast ISO when flying at jet speed over the car! I tried to get some but never could. They asked me how high I wanted to take pictures & I said 5' 3". He didn't understand me & I had to explain. He told me I was the only one who ever wanted it for normal photography.

That last smaller negative camera they came out with followed their lowering everything to their standards approach to the public. If you held the prints out at arms length they were just tolerable but you never kept them.

Dec 27, 2017 16:31:02 #

Shutterbug57 wrote:

.../... Is it photographers that started in digital and want to try film, but are uncomfortable with grain because they see it as the analog version of noise - and therefore it must be stomped out? .../...

Actually the search for no grain preceded the digital for decades. Think of all the low ISO films (B&W or color) made specifically for that purpose.

You also suffer from a misconception. Photographers in the digital age would love to see the randomization of noise vs the ridiculous squares. Some filter companies try to create that w/o success: a digital image reverts everything to little ugly pegs.

This might be a reason why digital cameras are still not as 'perfect' as some would want them to be.

Dec 27, 2017 16:53:48 #

Just like today digital cameras makers try to make them with little noise as possible back in the film days film manufacturers tried to make film with grain as fine as possible. Neither grain or noise is a desirable characteristic.

Dec 27, 2017 22:54:45 #

bpulv wrote:

Growing up in a digital world, you got it backward... (show quote)

I dunno. I shot Tri-X for B&W from the 1970s through about 2005 when I more or less switched to digital to cover my kids events. I have always liked the journalistic look and feel of Tri-X. Now for color, I prefer a more grain-free look - Velvia until I run out - then Ektar or Portra depending on what I am shooting. Different strokes.

Dec 27, 2017 23:08:35 #

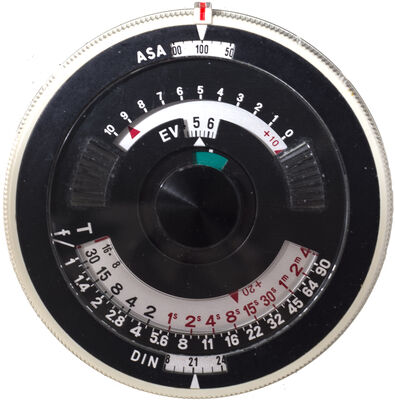

A very dear friend just gave me her fathers Lecia 111 as a Christmas present. I haven’t shot film for 30 years and I’m going to start again. I got some Berggar Pancro 400 B&W film the other day. I had never heard of it before. It has some great reviews about having very fine grain and being a little forgiving. She also gave me a light meter and the original manuals. The camera has just been gone through. It’s in incredible shape for being made in 1939. Should be a lot of fun. I also got out my Pentax K1000. Has anyone used this Berggar film or should I just go with the Tri x? It’s kind of funny that shooting film is a little intimidating. Going to try to develop at home and used a scanner to print off of.

Jan 12, 2018 12:22:34 #

TMax was around well before digital, and anyway the chase for finer grain predates digital.

Jan 12, 2018 17:13:13 #

I am a professional commercial/portrait photographer who has worked with black and white films and processing methodologies for a lifetime. I started messing around in my basement darkroom at the age of 12, my first studio apprentice job started off in the darkroom and I spent the better part of 50 years shooting film and working in the darkroom, so I hope y'all will enjoy my take on this question.

Due to market demands and business practicalities, I made the complete transition into digital photography about ten year ago and finally and somewhat reluctantly closed down my black and white darkroom and my analog/chemical color lab at my studio.

Suffice it to say that digital photography is a vastly different medium but for all intents and purposes, I can reproduce, replicate or imitate most of the effects and qualities that I archived with film in the digital medium- and then some! So I don't pine for the “good old days”. The aesthetics of printing are still the same and the degree of manipulations in digital work are even grater in scope that those that were obtainable in the old process. I do miss some of the old classical papers and chemicals and some of the craftsmanship involved in the process but we all need to use what is presently at our disposal. It is not easily practicable to manufacture traditional silver based printing papers but some workers are still willing to mix certain developer form “scratch” formulas if the can obtain the basic chemicals in photography types. So.. this is all I will say about digital, for the most part, because now, to stay on topic, we are gonna talk FILM!

First I will tell y'all something about FINE GRAIN. I have discovered long ago, that many medium to even high speed films can produce very fine grain results if processed very precisely and the WET TIME, during processing is minimized. There is a processing fault called RETICUALTION that is usually recognized in its extreme form caused by significant processing errors due to accidental high temperatures in the chemicals or especially the final washrag of the film. Severe reticulation shows up as extremely course grain that occurs when high temperatures in the chemistry or wash water causes the emulation to swell and begin separating from the film base. Most experienced dark room operators will not over heat or “boil” the film but this kind of emulsion swelling and resulting coarse grain can occur in more subtle ways if there is too much of a temperature differential between the chemical baths, if the acidity in the stop bath or the fixer is too high thus shocking the emulsion witch is in an alkaline state when it leaves the developer, if the film is overly immersed (for too long a time) in the stop bath, fixer, the hypo clearing agent, the wash water and/or the wetting agent.

So...here's my big secret. I was getting large format-like results as to acutance (sharpness) and virtual grain-less-ness with most films up to ISO 400 or even pushed to 800 or more- even in 35mm and medium format. I did this by simply maintaining consistent and precise temperature control at 68°F (20°C) in all the film processing solution right down to the wash water. Here's a few more tips and precautions: I maintain the same precise control on the TIMING in each bath as well. Most workers will be very accurate on development times but get a but get a bit sloppy in the other baths. Unnecessarily extended wet time brings about more graininess. Avoid using stop bath, fixer or hypo clearing agent as holding baths. Reduce the acidity in the stop bath or just use plain water and get the film into the fixer ASAP. Use standard fixer rather that rapid fixer- it has less tendency to shock the emulsion. The fixing time just needs to be the same as the clearing time- not longer- just make sure the kind of milky look of the film is gone and the bluish dye in the base is cleared. The function of hypo cleaning agent or other washing aids is to cut down on washing time, neutralize any remaining acidity in the film. It does this by softening the emulsion so it is wise to strictly control the time and temperature that is advised by the manufacturer and not extend the time unnecessarily. The same goes for Phot-Flo or similar wetting agents. Usually 30 second to one minute is the maximum time the film should remain in this solution. Rough squeegeeing and heat drying should be avoided. A very soft viscose sponge should be used if squeegeeing is required and room temperature air drying is best. Advanced workers may consider obtaining, improvising or building a filtered air drying cabinet. In-line wash water filtration is helpful in that water impurities or very hard water can also effect negative quality or cause staining. After using a washing aid or hypo eliminator, washing time shroud not exceed 5 or 10 minutes.

I usually would mix and dilute my processing chemicals with de-mineralized or distilled water to avoid staining and premature oxidation of the chemicals- they last longer.

AGITATION: Remember, you developing tank is not a Martini-shaker or a cake mixing bowel. Agitation in all processing baths is necessary for even processing and proper activity of the chemicals, however, over or violent agitation will cause many inconsistencies, streaks, over development and unnecessarily course grain. In most rotary/spool type tanks, an alternating rotating and up and down GENTLE agitation should be carried out for 5 seconds every 30 seconds or 10 seconds every minute- depending on the film/developer recommendations. The same time increments or sequences is recommended for tank/film hanger processing with GENTLE vertical dip-and dunk movements and rocking actions with tapping to dispel air-bells.

Processing temperature can be controlled and held by use of a water jacket, that is, you can use a sink or improvise a tank to contain all of your developing tanks and chemical containers. Filling this vessel with enough water of the proper temperature, can maintain temperatures for hours. Serious and advanced workers will want to invest in a temperature control valve of faucet system which automatically maintains water temperature and flow by means of a bi-metallic or electronic system. There are also thermometer wells that can be easily installed on an ordinary mixing faucet whereby water temperature can me monitored and controlled manually.

It takes a bit of patience and effort but this kind of processing will yield finer grain and the grain that does appear will be tighter and more pleasing. Grain clumps result for faulty processing. Precision processing will also yield better density and contrast control and enable easier printing.

Film type and brands? Well- y'all film buffs gotta admit that there is not nearly the kind of choices we had back in the day- most of it, alas, is gone. Listen folks, I, an many of my contemporaries (old photographers) can write books on film characteristics- not only grain but characteristic curves, D log E charts, chromatic sensitives of black and white films film and developer combinations but most of this stuff and the literature are long gone. It it is what is is and you have to work with what you have if you are still interested in crafting images with film.

Use to be, the rule of thumb was that slow speed fine grain had a bit more intrinsic contrast – like Plus-X and Pantomimic-X. Faster films like Tri-X had coarser grain and less contrast- some preferred the better potential for gradations of tone. The T-Max line came about as a result of what was touted as T-Grain manufacturing technology which ostensibly offered high speed and less grain. If both films lines are still available (?) I feel it is a matter of taste and which compatible chemicals are still readily available unless you are willing and able to mix things from scratch. In the olden days, films that were specified as “Professional”, at least by Kodak and Fugi, usually had a base that had a surface or “tooth” for (manual) negative retouching- this oftentimes had a bit more accompanying grain. The T-Max line was touted as being more “scan-able” for integration into digital retouching, editing and printing.

As for nostalgia- my all time favorite general purpose black and white film was, believe it or not, Verichrome-Pan, perhaps a cult favorite among pictorial photographers. At a modest ISO of about 100, it had incredible latitude, outrageous tonal range and tight and fine grain. Processed D-76 1:1, it yielded great sharpness and tonality even at significant degrees of enlargement. Verichrome-Pan processed in Pyro- MAGIC! Shadow detail up the wazoo!

Films like Technical Pan were virtually grain-less but there were very slow and kinda weird in that the had ultra-red sensitivity so it would render normal skin tones as almost porcelain white- if that's what you like. It could be processed in high a contrast method so that it would turn it into lith-film.

Now, suppose you like GRAIN! Ain't nothing wrong with that! Here's the deal and the history. In the late 1950s and early 1960, there was a great revolution in photojournalism, war coverage and press photography. Existing light became the buzz word and flash- was beginning to get a bad rap for artificiality and flatness in lighting. Large format press camera gave way to medium format usage and finally 35mm became the mainstay for news photographers and photojournalists. Everyone wanted to be able to photograph “a black cat in a coal mine at midnight” kinda thing. F/1.0 and f/.95 lenses began to emerge but when depth of field and hand-hold-able shutter speeds were required, the trend went toward very fast films and pushed processing in “dynamite” developers. Tri-X, Royal-Pan-X or Kodak “Recording Film 2475” pushed to ISO 3600 or more in Diafine (Red), Ethol, UFG or Acufine yielded negatives with golf -ball like granularity but who cared, the object was to get the image and tell the story- “who needs stinking shadow detail and fine grain”! Got so that press images that were not shot during a riot or in a war zone under the cover of darkness, were expected to be grainy nonetheless, otherwise they might have been interpreted or misconstrued a “not authentic enough”. In some cases it became an affectation or artifice. I worked at a newspaper for a time and my editors used to say who cares about grain- we are printing with a 55 line screen on “toilet paper” meaning a basically low resolution reproduction method on newsprint paper. Some photographers routinely forced course gran or printed images through a Mortensen kinda texture screen.

Other photographers hold the viewpoint that grain is like brush strokes in oil paintings or scratches on etchings- it's just part and parcel of the medium of film- I'm cool with that. I suppose it depends on the mood you want to create, the subject matter and the style you wish to adopt. There were and still are printing papers with surface textures that somewhat add to the look of a grainy image- you are the artist and it's up to you.

Another aspect of grain control is the type of light source in your enlarger, that is, if you are still printing in an analog/optical enlarger. A (rare) point source lamp house maximizes the rendition of grain structure. Next in line is a a condenser enlarger. A diffusion enlarger or a cold light type of lamp-house will minimize grain as well as dust and surface defect that may be on the negative. Grain is also accentuated by using an enlarging paper of a higher than normal contrast grade.

I hope this helps. Best regards.

Ed

Due to market demands and business practicalities, I made the complete transition into digital photography about ten year ago and finally and somewhat reluctantly closed down my black and white darkroom and my analog/chemical color lab at my studio.

Suffice it to say that digital photography is a vastly different medium but for all intents and purposes, I can reproduce, replicate or imitate most of the effects and qualities that I archived with film in the digital medium- and then some! So I don't pine for the “good old days”. The aesthetics of printing are still the same and the degree of manipulations in digital work are even grater in scope that those that were obtainable in the old process. I do miss some of the old classical papers and chemicals and some of the craftsmanship involved in the process but we all need to use what is presently at our disposal. It is not easily practicable to manufacture traditional silver based printing papers but some workers are still willing to mix certain developer form “scratch” formulas if the can obtain the basic chemicals in photography types. So.. this is all I will say about digital, for the most part, because now, to stay on topic, we are gonna talk FILM!

First I will tell y'all something about FINE GRAIN. I have discovered long ago, that many medium to even high speed films can produce very fine grain results if processed very precisely and the WET TIME, during processing is minimized. There is a processing fault called RETICUALTION that is usually recognized in its extreme form caused by significant processing errors due to accidental high temperatures in the chemicals or especially the final washrag of the film. Severe reticulation shows up as extremely course grain that occurs when high temperatures in the chemistry or wash water causes the emulation to swell and begin separating from the film base. Most experienced dark room operators will not over heat or “boil” the film but this kind of emulsion swelling and resulting coarse grain can occur in more subtle ways if there is too much of a temperature differential between the chemical baths, if the acidity in the stop bath or the fixer is too high thus shocking the emulsion witch is in an alkaline state when it leaves the developer, if the film is overly immersed (for too long a time) in the stop bath, fixer, the hypo clearing agent, the wash water and/or the wetting agent.

So...here's my big secret. I was getting large format-like results as to acutance (sharpness) and virtual grain-less-ness with most films up to ISO 400 or even pushed to 800 or more- even in 35mm and medium format. I did this by simply maintaining consistent and precise temperature control at 68°F (20°C) in all the film processing solution right down to the wash water. Here's a few more tips and precautions: I maintain the same precise control on the TIMING in each bath as well. Most workers will be very accurate on development times but get a but get a bit sloppy in the other baths. Unnecessarily extended wet time brings about more graininess. Avoid using stop bath, fixer or hypo clearing agent as holding baths. Reduce the acidity in the stop bath or just use plain water and get the film into the fixer ASAP. Use standard fixer rather that rapid fixer- it has less tendency to shock the emulsion. The fixing time just needs to be the same as the clearing time- not longer- just make sure the kind of milky look of the film is gone and the bluish dye in the base is cleared. The function of hypo cleaning agent or other washing aids is to cut down on washing time, neutralize any remaining acidity in the film. It does this by softening the emulsion so it is wise to strictly control the time and temperature that is advised by the manufacturer and not extend the time unnecessarily. The same goes for Phot-Flo or similar wetting agents. Usually 30 second to one minute is the maximum time the film should remain in this solution. Rough squeegeeing and heat drying should be avoided. A very soft viscose sponge should be used if squeegeeing is required and room temperature air drying is best. Advanced workers may consider obtaining, improvising or building a filtered air drying cabinet. In-line wash water filtration is helpful in that water impurities or very hard water can also effect negative quality or cause staining. After using a washing aid or hypo eliminator, washing time shroud not exceed 5 or 10 minutes.

I usually would mix and dilute my processing chemicals with de-mineralized or distilled water to avoid staining and premature oxidation of the chemicals- they last longer.

AGITATION: Remember, you developing tank is not a Martini-shaker or a cake mixing bowel. Agitation in all processing baths is necessary for even processing and proper activity of the chemicals, however, over or violent agitation will cause many inconsistencies, streaks, over development and unnecessarily course grain. In most rotary/spool type tanks, an alternating rotating and up and down GENTLE agitation should be carried out for 5 seconds every 30 seconds or 10 seconds every minute- depending on the film/developer recommendations. The same time increments or sequences is recommended for tank/film hanger processing with GENTLE vertical dip-and dunk movements and rocking actions with tapping to dispel air-bells.

Processing temperature can be controlled and held by use of a water jacket, that is, you can use a sink or improvise a tank to contain all of your developing tanks and chemical containers. Filling this vessel with enough water of the proper temperature, can maintain temperatures for hours. Serious and advanced workers will want to invest in a temperature control valve of faucet system which automatically maintains water temperature and flow by means of a bi-metallic or electronic system. There are also thermometer wells that can be easily installed on an ordinary mixing faucet whereby water temperature can me monitored and controlled manually.

It takes a bit of patience and effort but this kind of processing will yield finer grain and the grain that does appear will be tighter and more pleasing. Grain clumps result for faulty processing. Precision processing will also yield better density and contrast control and enable easier printing.

Film type and brands? Well- y'all film buffs gotta admit that there is not nearly the kind of choices we had back in the day- most of it, alas, is gone. Listen folks, I, an many of my contemporaries (old photographers) can write books on film characteristics- not only grain but characteristic curves, D log E charts, chromatic sensitives of black and white films film and developer combinations but most of this stuff and the literature are long gone. It it is what is is and you have to work with what you have if you are still interested in crafting images with film.

Use to be, the rule of thumb was that slow speed fine grain had a bit more intrinsic contrast – like Plus-X and Pantomimic-X. Faster films like Tri-X had coarser grain and less contrast- some preferred the better potential for gradations of tone. The T-Max line came about as a result of what was touted as T-Grain manufacturing technology which ostensibly offered high speed and less grain. If both films lines are still available (?) I feel it is a matter of taste and which compatible chemicals are still readily available unless you are willing and able to mix things from scratch. In the olden days, films that were specified as “Professional”, at least by Kodak and Fugi, usually had a base that had a surface or “tooth” for (manual) negative retouching- this oftentimes had a bit more accompanying grain. The T-Max line was touted as being more “scan-able” for integration into digital retouching, editing and printing.

As for nostalgia- my all time favorite general purpose black and white film was, believe it or not, Verichrome-Pan, perhaps a cult favorite among pictorial photographers. At a modest ISO of about 100, it had incredible latitude, outrageous tonal range and tight and fine grain. Processed D-76 1:1, it yielded great sharpness and tonality even at significant degrees of enlargement. Verichrome-Pan processed in Pyro- MAGIC! Shadow detail up the wazoo!

Films like Technical Pan were virtually grain-less but there were very slow and kinda weird in that the had ultra-red sensitivity so it would render normal skin tones as almost porcelain white- if that's what you like. It could be processed in high a contrast method so that it would turn it into lith-film.

Now, suppose you like GRAIN! Ain't nothing wrong with that! Here's the deal and the history. In the late 1950s and early 1960, there was a great revolution in photojournalism, war coverage and press photography. Existing light became the buzz word and flash- was beginning to get a bad rap for artificiality and flatness in lighting. Large format press camera gave way to medium format usage and finally 35mm became the mainstay for news photographers and photojournalists. Everyone wanted to be able to photograph “a black cat in a coal mine at midnight” kinda thing. F/1.0 and f/.95 lenses began to emerge but when depth of field and hand-hold-able shutter speeds were required, the trend went toward very fast films and pushed processing in “dynamite” developers. Tri-X, Royal-Pan-X or Kodak “Recording Film 2475” pushed to ISO 3600 or more in Diafine (Red), Ethol, UFG or Acufine yielded negatives with golf -ball like granularity but who cared, the object was to get the image and tell the story- “who needs stinking shadow detail and fine grain”! Got so that press images that were not shot during a riot or in a war zone under the cover of darkness, were expected to be grainy nonetheless, otherwise they might have been interpreted or misconstrued a “not authentic enough”. In some cases it became an affectation or artifice. I worked at a newspaper for a time and my editors used to say who cares about grain- we are printing with a 55 line screen on “toilet paper” meaning a basically low resolution reproduction method on newsprint paper. Some photographers routinely forced course gran or printed images through a Mortensen kinda texture screen.

Other photographers hold the viewpoint that grain is like brush strokes in oil paintings or scratches on etchings- it's just part and parcel of the medium of film- I'm cool with that. I suppose it depends on the mood you want to create, the subject matter and the style you wish to adopt. There were and still are printing papers with surface textures that somewhat add to the look of a grainy image- you are the artist and it's up to you.

Another aspect of grain control is the type of light source in your enlarger, that is, if you are still printing in an analog/optical enlarger. A (rare) point source lamp house maximizes the rendition of grain structure. Next in line is a a condenser enlarger. A diffusion enlarger or a cold light type of lamp-house will minimize grain as well as dust and surface defect that may be on the negative. Grain is also accentuated by using an enlarging paper of a higher than normal contrast grade.

I hope this helps. Best regards.

Ed

Jan 12, 2018 17:32:54 #

E.L.. Shapiro wrote:

I am a professional commercial/portrait photograph... (show quote)

Ed - lots of good info. Thanks. Below is an image I recently shot on Tri-X and processed with Ilfosol 3 @ 14:1, Kodak stop bath and Kodak fixer. It has a level of grain I like & itâs clearly film. Shot with a Mamiya 645 & digitized with a D500 & light table.

Jan 12, 2018 17:35:26 #

Thanks very interesting. One of my hobbies used to be testing lenses. I have tested a couple hundred lenses including many Leica and zeiss lenses. I was surprised to see the sumy as your sharpest lens. Modern photography used to rate 88 l/mm as excellent. Most of my Leica lenses rated as excellent but the only lens I tested that approached 200 l/mm was a lowly Pentax 100mm f2.8. It even exceeded Leica Sumys and 100 apo macro. This whole subject has gotten me interested in shooting film again I still have an entire freezer full. I guess I’ll get out my large and medium format stuff out again.

Jan 12, 2018 19:43:58 #

I do, fondly remember all the lens tests that were published in the now defect Modern Photography Magazine. The had one heck of a testing facility at their New York headquarters. The kind of interesting and somewhat kinda contradictory, paradoxical or perhaps oxymoronic about many of the reported lens resolution specifications is that there were, back in the day, very few if any, general purpose films that could resolve that kind of detail.

There were a number of special purpose lithographic films, very slow technical films and some very specialized emulsions like those used in the production of printed circuits that did have outrageous resolutions potential but they were usually extremely slow- I remember one with an IOS index of 3 or 6 depending on the developer. They were often designed for spectral sensitivity in what I called exotic light sources- carbon arc and other stuff used in the graphic arts industry or in scientific labs. I recall finding out that a special film used for printed circuit manufacturing was great for coping badly faded sepia type prints because of it higher contrast and extreme sensitivity to yellow. I think it had an ISO rating of 10.

I also recall, upon the introduction of Kodak's and Fuji's introduction of their T-Grain films in both color negative and black and white films, I really began to appreciate the performance of my Hasselblad medium format equipment. i used to joke that my older Ziess lenses were like old Stradivarius violins- like as if they improve with age as long as you keep using them. The newer generation of films did make quite the difference, not only in grain structure but in color saturation, palettes and dynamic range potential. it was like I woke up one morning and found out that all my lenses were "magically" sharper.

Another note of nostalgia- in that Modern Photography lab they used to totally disassemble cameras and lenses and put them back together again just to see how the work, how there are made and if the are as good as the are said to be. Nowadays, I don't even know of a camera repair shop that can actually troubleshoot and fix some of our latest cameras. i suppose some of them are just parts changers. It's crazy- you buy a multi thousand dollar camera and it just expires one day like an old car that is beyond repair. This adds new meaning to "built in obsolescence"- it's more like built in self destruction! I wonder of any of our current cameras and lenses will survive long enough to become classics, user-collectibles or antiques.

Perhaps something for another thread?

There were a number of special purpose lithographic films, very slow technical films and some very specialized emulsions like those used in the production of printed circuits that did have outrageous resolutions potential but they were usually extremely slow- I remember one with an IOS index of 3 or 6 depending on the developer. They were often designed for spectral sensitivity in what I called exotic light sources- carbon arc and other stuff used in the graphic arts industry or in scientific labs. I recall finding out that a special film used for printed circuit manufacturing was great for coping badly faded sepia type prints because of it higher contrast and extreme sensitivity to yellow. I think it had an ISO rating of 10.

I also recall, upon the introduction of Kodak's and Fuji's introduction of their T-Grain films in both color negative and black and white films, I really began to appreciate the performance of my Hasselblad medium format equipment. i used to joke that my older Ziess lenses were like old Stradivarius violins- like as if they improve with age as long as you keep using them. The newer generation of films did make quite the difference, not only in grain structure but in color saturation, palettes and dynamic range potential. it was like I woke up one morning and found out that all my lenses were "magically" sharper.

Another note of nostalgia- in that Modern Photography lab they used to totally disassemble cameras and lenses and put them back together again just to see how the work, how there are made and if the are as good as the are said to be. Nowadays, I don't even know of a camera repair shop that can actually troubleshoot and fix some of our latest cameras. i suppose some of them are just parts changers. It's crazy- you buy a multi thousand dollar camera and it just expires one day like an old car that is beyond repair. This adds new meaning to "built in obsolescence"- it's more like built in self destruction! I wonder of any of our current cameras and lenses will survive long enough to become classics, user-collectibles or antiques.

Perhaps something for another thread?

If you want to reply, then register here. Registration is free and your account is created instantly, so you can post right away.